Christmas at the Fort

What would visitors at both the modern-day replica and the original Fort Whoop-Up have seen and experienced during the holiday season?

What would visitors at both the modern-day replica and the original Fort Whoop-Up have seen and experienced during the holiday season? Join staff as they explain what historical and modern Christmas experiences at the fort included! From community feasts hosted by Joe Healy to hand-dipping wax candles and making Christmas crackers.

The Galt is grateful to the subject-matter experts delivering online content. As local professionals and knowledge experts, these presenters add valuable contributions to the local discourse; however, their ideas are their own. The people featured in the videos and those behind the scenes followed best practices to protect their health and safety.

Kítao’ahsinnooni (Blackfoot Territory)

Rebecca Many Grey Horses presents an overview of Indigenous history in southern Alberta.

Rebecca Many Grey Horses presents an overview of Indigenous history in southern Alberta. Rebecca has facilitated Indigenous history classes here at the Galt for the past two years, bringing in local experts, knowledge keepers and Elders to educate large groups of learners.

The video features many archival images. You can find more information about the photos on our database website at https://collections.galtmuseum.com.

The hand-drawn map of traditional Blackfoot territory can be purchased for $10 by contacting Mary Weasel Fat, Librarian and Elders Coordinator at 403.737.4351.

The Galt is grateful to the subject-matter experts delivering online content. As local professionals and knowledge experts, these presenters add valuable contributions to the local discourse; however, their ideas are their own. The people featured in the videos and those behind the scenes followed best practices to protect their health and safety.

Sacred Niitsitapi Sites

Southern Alberta is traditional Niitsitapi, or Blackfoot, territory. Rebecca Many Grey Horses discusses the importance of several sites including Chief Mountain, Crowsnest peak, Devil's Thumb, the Sweetgrass Hills, Writing on Stone, Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump, as well as the significance of medicine wheels and tepee rings.

Southern Alberta is traditional Niitsitapi, or Blackfoot, territory. Rebecca Many Grey Horses discusses the importance of several sites including Chief Mountain, Crowsnest peak, Devil's Thumb, the Sweetgrass Hills, Writing on Stone, Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump, as well as the significance of medicine wheels and tepee rings.

The Galt is grateful to the subject-matter experts delivering online content. As local professionals and knowledge experts, these presenters add valuable contributions to the local discourse; however, their ideas are their own. The people featured in the videos and those behind the scenes followed best practices to protect their health and safety.

Niitsitapi and Epidemics

The Niitsitapi, or Blackfoot people, have been hit repeatedly by epidemics. Rebecca Many Grey Horses shares her research about the impact of smallpox, measles, scarlet fever and the Spanish flu.

The Niitsitapi, or Blackfoot people, have been hit repeatedly by epidemics. Rebecca Many Grey Horses shares her research about the impact of smallpox, measles, scarlet fever and the Spanish flu.

Learn more about the Spanish Flu Pandemic in southern Alberta in our online exhibit Pandemic at Home: The 1918–1919 Flu.

The Galt is grateful to the subject-matter experts delivering online content. As local professionals and knowledge experts, these presenters add valuable contributions to the local discourse; however, their ideas are their own. The people featured in the videos and those behind the scenes followed best practices to protect their health and safety.

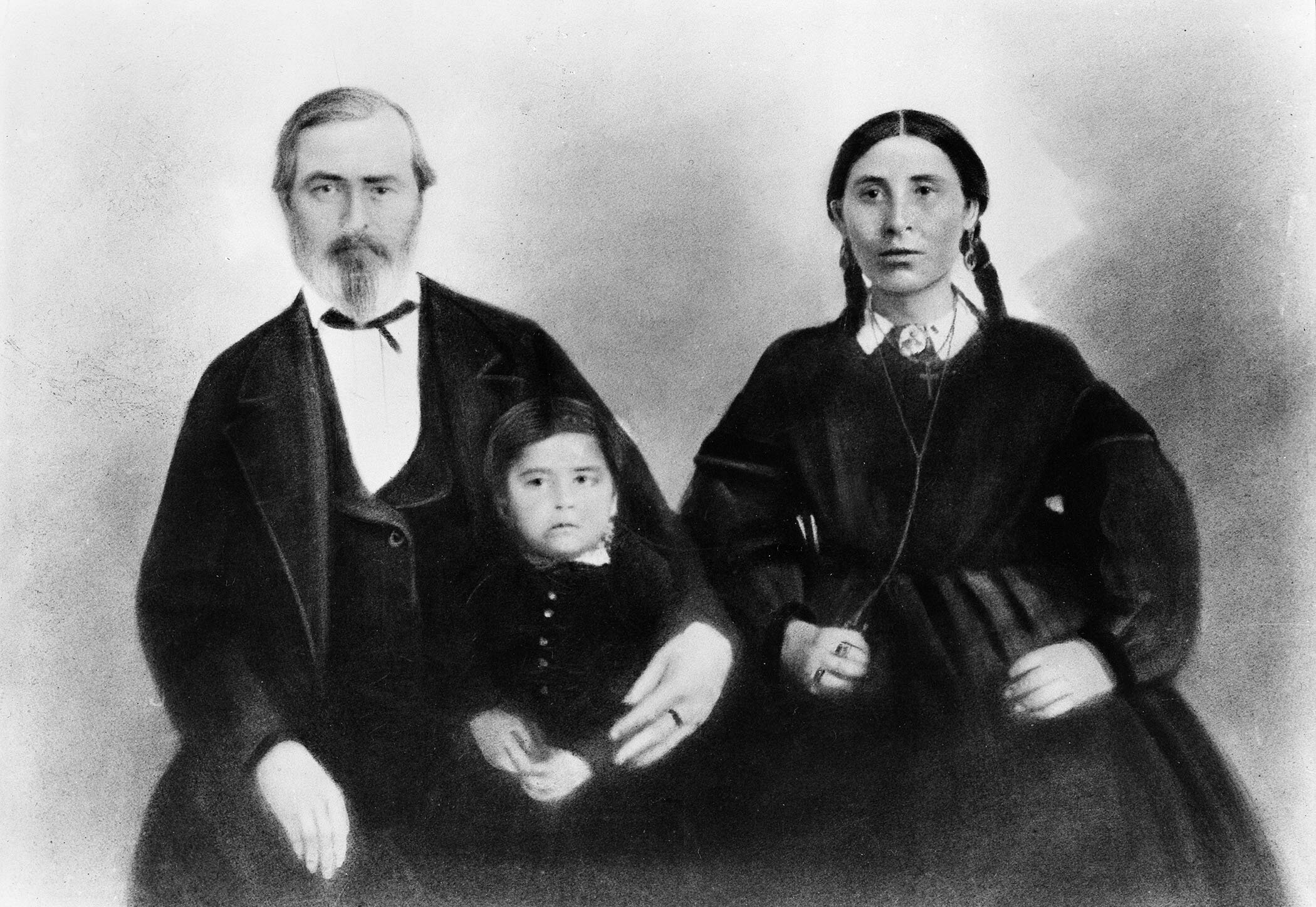

Natawista (Holy Snake Woman), Peacemaker

A diplomat and mother, Natawista played a key role in helping establish treaties and navigate negotiations between American and British traders with Blackfoot tribes.

Natawista with Alexander Culbertson and son Joe, taken circa 1863.

Photo courtesy of the Montana Historical Society Research Center Photograph Archives: 941-818.

A diplomat and mother, Natawista played a key role in helping establish treaties and navigate negotiations between American and British traders with Blackfoot tribes. She was born around 1824 in traditional Blackfoot territory, probably in what is now known as southern Alberta. Her father was Chief Stoó-kya-tosi (Two Suns), who was sometimes known as Sun Old Man and Father of Many Children.

When Natawista was around sixteen years old, she was married to Alexander Culbertson in 1840. Culbertson was the chief trader for the Upper Missouri Outfit of the American Fur Company. Because of the intense competition between American and British traders for the Blackfoot trade, it had become common for officers to marry the daughters of chiefs to cement trading relations.

In 1843, naturalist John James Audubon met Natawista at Fort Union (Fort Union Trading Post, North Dakota) on the upper Missouri River and referred to her as a “princess… possessed of strength and grace in a marked degree.” Eight years later Swiss artist Rudolf Friedrich Kurz described her as “one of the most beautiful [Indigenous] women. She would be an excellent model for a Venus.”

In 1854, Natawista insisted on accompanying a party of United States government negotiators led by her husband to the Blackfoot camps. “I am afraid that they and the whites will not understand each other,” she said, “but if I go, I may be able to explain things to them, and soothe them if they should be irritated. I know there is great danger.” Partly because of her efforts, a treaty was signed a year later.

During their years together, Natawista and Culbertson had five children. At some time after 1870, Natawista went to the Blood camps and never returned to her husband. She lived with her nephew Mékaisto (Red Crow) and her extended family for much of the remainder of her life.

You can find out more about Blackfoot historical figures and culture at our Indigenous History Program led by Rebecca Many Grey Horses at the Galt Museum & Archives on Tuesdays from 10:30–noon until the end of October.

Potai’na (Flying Chief), or Joe Healy

Potai’na (Flying Chief), also known as Joseph Healy, was a prominent member of the Kainai Nation and son of Akai-nuspi (Many Braids) and Pi’aki (the Dancer).

Potai’na (Flying Chief), also known as Joseph Healy, was a prominent member of the Kainai Nation and son of Akai-nuspi (Many Braids) and Pi’aki (the Dancer). Potai’na was orphaned at a young age when his parents and sisters were killed in their camp near Sun River, MT. It was his father’s dying wish that he be taken in by John Healy who at the time was operating a trading post in Sun River. Potai’na was adopted by Mary-Frances and Johnny Healy (who along with A. B. Hamilton started Fort Whoop-Up) and they gave him the name Joseph. Joe was sent to school in nearby Fort Shaw, Montana and learned to speak and write English. He worked with his adopted father at both the Sun River trading post and later at Fort Whoop-Up. He also served as a scout and interpreter for the North-West Mounted Police. Later in life he spoke with a newspaper reporter and relayed some memories of Fort Whoop-Up:

“I was only a boy then but I remember well the long wagon trains loaded high with goods and supplies. It was a two week trip for us [from Fort Benton], and we passed through many dangers. I was at the useful stage and knew well how to handle the four-horse team.”

As a youth, he was an eyewitness to the 1870 battle between the Blackfoot and the Cree in what is now Indian Battle Park.

“I had lived there (Fort Whoop-Up) just like a white man, a son of the family of Mr. Healy. I attended the white schools of Montana, and not till years after did the longing come to me to return to Canada to see my remaining relatives and friends.”

Healy lived the latter part of his life on the Blood Reserve. Although he was never an official chief, Joe Healy was one of the great leaders of the Kainai people. He and his wife, Toopikiini (Nostrils), raised ten children and many of their descendants remain in southern Alberta today.

Constructing the Fort

William Gladstone (“Old Glad”) was the head carpenter and blacksmith at Fort Whoop-Up. He was a former carpenter and boat builder for the Hudson’s Bay Company, and he was hired in Fort Benton in the early summer of 1870 for the two-year project of building the bigger, more permanent Fort Whoop-Up.

William James Shanks Gladstone "Old Glad" in a seated portrait holding a small child.

Galt Museum & Archives, 19754242000

William Gladstone (“Old Glad”) was the head carpenter and blacksmith. He was a former carpenter and boat builder for the Hudson’s Bay Company, and he was hired in Fort Benton in the early summer of 1870 for the two-year project of building the bigger, more permanent fort at the junction of the Oldman and St. Mary Rivers as a winter camp, also known as Ákáí’nissko (Many Deaths Place).

This larger fort was built using about 6,000 squared cottonwood logs. Buildings faced inward to an open central square. There was a kitchen, trading room, robe storage room, warehouse, gun loft, blacksmith shop, living quarters, and “deep roomy cellars” for the furs. There was also stabling for the horses. Animals were important at the fort and included oxen, horses and a few dogs. The fort reportedly kept pigs to help manage the rattlesnake population.

Local blacksmith Tim Wickstrom works the forge at Fort Whoop-Up.

Photo by Fot Whoop-Up and Galt Museum & Archives / Graham Ruttan

Even though the fort was designed and used for trade, it incorporated elements of military forts intended for defence. It was enclosed by a palisade with a heavy oak gate on one side, bastions at two opposing corners, and featured loopholes, high windows, and bars over the chimneys. The Whoop-Up flag flew over a corner bastion. The similarity to the American flag reportedly concerned the Canadian government and was a factor in plans to increase the government’s presence in the west.

The fort was equipped with two cannons: a 6-pounder on a naval carriage and a 2-inch muzzle-loader. The 2-inch cannon was fired to announce the arrival of bull trains arriving from Fort Benton with new trade goods.

2020 marks 150 years since Fort Whoop-Up was established. You can learn more about the history of the fort at https://fort.galtmuseum.com.

Local historian George Kush points at the replica of the 2-inch muzzle loader with Bill Peta leaning against the wheel.

Fort Whoop-Up and Galt Museum & Archives / Graham Ruttan

Bill Peta with the Fort Whoop-Up Black Powder Club loading a charge into the replica of the 2-inch muzzle loader.

Fort Whoop-Up and Galt Museum & Archives / Graham Ruttan

Ákáí’nissko (Many Deaths Place)

Niitsitapi used the area at the junction of the St. Mary and Belly, or Oldman, Rivers as a winter camp. The site was located along part of a traditional migration route known as the Old North Trail. It was known as Ákáí’nissko (Many Deaths Place).

The Milky Way from Cottowood Park in Lethbridge looking west toward the location of Ákáí’nissko and the original site of Fort Whoop-Up.

Photo by Graham Ruttan

Niitsitapi used the area at the junction of the St. Mary and Belly, or Oldman, Rivers as a winter camp. The site was located along part of a traditional migration route known as the Old North Trail. It was known as Ákáí’nissko (Many Deaths Place) after a smallpox epidemic in 1837 killed up to two-thirds of the Blackfoot people and was marked by many closed stone rings.

When tepees are set up, the base of the tepee is secured and protected from the wind by piling stones around the circular base of the tepee, with an opening in the ring for the door of the tepee. When people die in a tepee, the ring of stones is closed. The closed stone rings at Ákáí’nissko mark the places where people died of smallpox.

Trail Riders of the Canadian Rockies

Travel Alberta

In early 1870, Kainai leader Aka’kitsipimi’otas (Many Spotted Horses) gave permission to two American free traders, Alfred B. Hamilton and John J. Healy, to set up a trading post in Ákáí’nissko. A photograph taken by William Hook in April 1879 shows tepees to the east of Fort Whoop-Up with the proprietary designs of Aka’kitsipimi’otas.

Hamilton and Healy built a small trading post they initially called Fort Hamilton. This initial building was a simple 60-foot square structure with six rooms. The traders made huge profits in their first season and decided to expand into a larger and more permanent fort. After the first trading season, that initial structure was badly damaged by fire, and the new structure was built a short distance away. The construction of the new fort, which came to be known as Fort Whoop-Up, started later in 1870 and took about two years to complete.

2020 marks 150 years since Fort Whoop-Up was established. You can learn more about the history of the fort at https://fort.galtmuseum.com.

Tepee rings near Carmangay, Alberta.

Robert Strusievicz on Flickr

Crossing the Border

American free traders Alfred B. Hamilton and John J. Healy left Fort Benton in December 1869. They travelled for several weeks and in early 1870, they set up a trading post at the junction of the St. Mary and Belly, or Oldman, Rivers.

In 1865, the American Civil War ended and around the same time a gold rush in Montana attracted primarily young men to the region in search of gold and opportunity. Fur traders in Montana had been illegally trading whisky with the Blackfoot in exchange for buffalo robes. In the late 1860s the US Government cracked down on the illegal whisky trade in Montana, which inspired many traders to flee the law and continue the trade across the border in Canada.

American free traders Alfred B. Hamilton and John J. Healy left Fort Benton in December 1869. They travelled for several weeks along what would later become the Whoop-Up Trail. In early 1870, they set up a trading post at the junction of the St. Mary and Belly, or Oldman, Rivers.

Exterior view of the original Fort Whoop-Up south of Lethbridge, c. 1883.

Galt Museum & Archives, 19760213002

They received permission from Kainai leader Aka’kitsipimi’otas (Many Spotted Horses) to establish the fort at that location, which was a favourite wintering camp of the Niitsitapi (Real People or Blackfoot People).

For the next several years, Fort Whoop-Up became the centre of the American robe and whisky trade system in what is now southern Alberta. Other trading forts in the region included Slide Out, Standoff, and Robbers’ Roost.

2020 marks 150 years since Fort Whoop-Up was established. The anniversary provides an occasion for rethinking how the history of the fort has been told. A lot of lore and stories have arisen regarding happenings at the Fort. Not all of the tales can be substantiated, but those that can be paint a complex picture of life on the prairies for American, Canadian and European traders and the Blackfoot and Métis who traded with them.

The original site of Fort Whoop-Up near the confluence of the St. Mary and Oldman Rivers in 2020.

Fort Whoop-Up and Galt Museum & Archives / Graham Ruttan

Traditional Ways of Living

What are the traditional ways of living of the Niitsitapi (Blackfoot)? Fort Whoop-Up tells visitors about the history, culture and traditions of the Niitsitapi.

An individual seated on a hill overlooking a Blackfoot Sundance Camp.

Galt Museum & Archives, 19871170000

There are four nations of Niitsitapi, the Kainai, Piikani, Siksika and Amskapi Pikuni (Blackfeet in Montana). Together these nations are known as the Siksikaitsitapi (Blackfoot Confederacy). The four Nations share customs, language and beliefs.

Traditional Blackfoot Territory extends from the North Saskatchewan River down to the Yellowstone River, and from the Rocky Mountains in the west to the Great Sand Hills in the east. Political boundaries in this territory were defined by watersheds and river tracts, rather than arbitrary property lines.

Prior to the arrival of Europeans, food was abundant on the prairies. It is estimated that there were upward of 70 million bison on the plains, as well as great numbers of elk, deer, antelope, moose, and diverse flora and fauna.

An individual riding a horse pulling a travois

Galt Museum & Archives, 19760215014

Niitsitapi were a’pawaawahkao’p (always on the move), and all travel was for a purpose. Prior to the introduction of the horse from the Shoshone people who acquired them from Spanish, Niitsitapi used wolves to pull travois as a means of transporting goods related to harvests, trade and ceremony. Wolves were captured, tamed and trained as pups. People would go to the wolf dens, wait for the adult wolves to leave, and insert sticks from the rose bush. They would move the sticks around until the thorns caught in the fur of the pups, and then they would pull out the rose sticks with a pup attached to them.

Niitsitapi had well established trade relationships with other First Nations prior to the fur trade, and a different economic culture. They did not engage in trading for a profit, but rather understood exchange as a form of building and maintaining good relationships.

Fort Whoop-Up tells the story of how the arrival of European traders and settlers changed these traditional ways of living of the Niitsitapi. 2020 marks 150 years since Fort Whoop-Up was established.

Fort Whoop-Up Cannon Belongs to the Citizens of Lethbridge

A key artifact in the telling of the Fort Whoop-Up story is the Three-Pounder Field Gun, also known as the Fort Cannon. The cannon is the most documented artifact connected to Lethbridge’s history.

Bill Peta from the Fort Whoop-Up Black Powder Club loading a replica cannon at Fort Whoop-Up.

Photo courtesy of Fort Whoop-Up.

May 18th is International Museum Day. It is a day to celebrate the preservation and sharing of objects and their stories. The volunteers and staff of the Galt are committed to this public service at the museum and now, at Fort Whoop-up. A key artifact in the telling of the Fort Whoop-Up story is the Three-Pounder Field Gun, also known as the Fort Cannon. The cannon is the most documented artifact connected to Lethbridge’s history.

The cannon was brought to Fort Whoop-Up country by whiskey traders and has resided as a part of Lethbridge’s history and heritage for close to 146 years. From the 1870s to 1892 the cannon was located at the original Fort Whoop-Up. From 1892 to 1929 it belong to Lethbridge resident John D. Higinbotham. In 1929 Higinbotham entrusted care of the cannon to the City of Lethbridge and the cannon it took its place in Galt Gardens.

The City of Lethbridge placed the artillery piece in the Sir Alexander Galt Museum’s collection in 1973. Where it was housed until the Fort Whoop Society requested its move to the Fort Whoop-Up replica in Indian Battle Park. In June 1997 a letter to the Fort Whoop-Up Interpretive Society noted “The Fort Whoop-Up Field Gun represents a unique artifact, significant in the interpretation of [the] facility’s mandate, as well as the origins of the present day community of Lethbridge. As a material resource, its historic value is priceless.” After much deliberation, ownership of the Fort Field Gun was transferred from the Galt to Fort Whoop-Up where its story continued to be told and could be enjoyed by citizens and visitors alike.

The cannon brings Lethbridge a deep connection to our citizens’ sense of place. The Galt Museum & Archives requested the return of only one artifact from the previous operators of the Fort Whoop-Up Interpretive Centre: the Three-Pounder fort cannon. This cannon is not relevant to other towns or cities. We encourage the society to reconsider and return the cannon to the City collection with the Galt Museum & Archives/Fort Whoop-up.

Finding Fort Whoop-Up

Much more of the story of Fort Whoop-Up has been lost to time, people and natural events.

Drone footage of the cairn and empty flag poles at the original site of Fort Whoop-Up.

In the fall of 2012, the exhibit at the Galt Museum & Archives Uncovering Secrets: Archaeology in Southern Alberta highlighted 15 sites and features, telling human stories found under the soils and across the landscape of the area, including the original Fort Whoop-Up.

By the late 1800s, buffalo hides used for warm coats and strong industrial belts became the major item of trade on the western plains. Between 1869 and 1874, there was no official Canadian presence preventing American traders from building Fort Hamilton and then, after Fort Hamilton burned down, from building Fort Whoop-Up nearby. There was no official presence preventing them from trading whiskey, guns, knives, blankets, beads, and food items with the Niitsitapi, or Blackfoot, in exchange for valuable bison robes.

With the arrival of the North West Mounted Police (NWMP) in 1874, most of the whiskey traders quit the business. From 1876 until 1888, when a fire destroyed much of the fort, the NWMP rented space to use as an outpost.

The site of the fort was surveyed and excavated by different archaeology teams in the 1970s, the 1980s and the 1990s.

The first team found the remains of a corner bastion, some segments of the original walls, as well as a stone-lined well.

The second team found a stable, a storeroom, and living quarters. They recovered some food-related artifacts and a variety of medicinal bottles used for personal alcohol consumption.

An archaeology team from the University of Lethbridge verified the dimensions of the fort and found charred soil, which confirmed that the 1888 fire had occurred in the NWMP quarters. The team excavated the trade room, uncovering buttons, ammunition, brass beads, and tacks. They also excavated trenches to determine the outline of the palisade surrounding the fort’s compound.

Much of the story of Fort Whoop-Up has been lost. Time literally eats away at items made of leather, wood, and other organic materials. Floods and loooting at the site has removed much of the material evidence of the fort.

Some artifacts related to Fort Whoop-up and other archeological sites are included in the collections at the Galt Museum & Archives at collections.galtmuseum.com.

Rebecca Many Grey Horses presents an overview of Indigenous history in southern Alberta.